Architecture and Landscape Architecture Come Together to Reimagine Closed Bronzeville Schools

In 2013 the City of Chicago approved the closure of 49 public elementary schools, the largest school closure in United States history. Reports showed that the move was most detrimental to the students who were moved from the shuttered schools, approximately two-thirds of which remain unused.

Acknowledging the impact of the mass school closure of 2013, a fifth-year architecture studio, led by Illinois Institute of Technology College of Architecture professors Dirk Denison and Maria Villalobos Hernandez, seeks, in collaboration with Chicago Commissioner of Planning and Development Maurice Cox, to find new solutions through architecture, landscape architecture, and urbanism to turn the unused schools into new opportunities for the neighborhoods where they are located.

The studio focuses on two of those closed schools: Overton Elementary and Parkman Elementary. Both occupy spaces on the southwest corner of the Bronzeville neighborhood near the eight-lane Dan Ryan Expressway and are separated from each other by a tract of land that was formerly part of the Robert Taylor Homes. Overton, designed in the 1960s by Chicago architecture firm Perkins+Will, is a Modernist, three-story building consisting of three glass and gloss brick towers, while Dwight H. Perkins created Parkman’s 1912 neo-traditional design.

“We went to Overton and Parkman because of their close proximity to each other and because this is on the other end of Bronzeville to Illinois Tech. It is still home to us and a part of our neighborhood that we're so fortunate to be in,” says Denison.

The studio’s aim was to look at the reuse of the schools holistically. It brought together students from all programs at the College of Architecture to consider not only the future of the buildings but also the urban landscape to which they belong. The course is interdisciplinary, multicultural, and multigenerational by design, with the aim being to open the field to ideas that better represent current challenges and generational aspirations. The developed frameworks conceive of the former schools as comprehensive campuses for music and art, food, local commerce, and recreation.

“The studio touched on multiple scales and it gave a lot of space to work with, and we were pushed to have intensive conversations to make the final outcome cohesive and integrated,” says Giovana Geluda (M.ARCH. 3rd Year). “Ultimately I learned a lot from the [landscape architecture students] we worked with, and it allowed us to create spaces for the community to get together and bond.”

Geluda’s team envisioned the Overton school and its surrounding spaces as a restoration of the native marshland that originally inhabited Chicago prior to urbanization. The restoration would not only reduce flooding in the area but also provide common spaces for neighbors to convene around water. In the proposal, Overton serves as a campus and entrypoint to the wetland space, an incubator for entrepreneurs living in the area, and a water research center to aid in the wetland recovery and draw public investments.

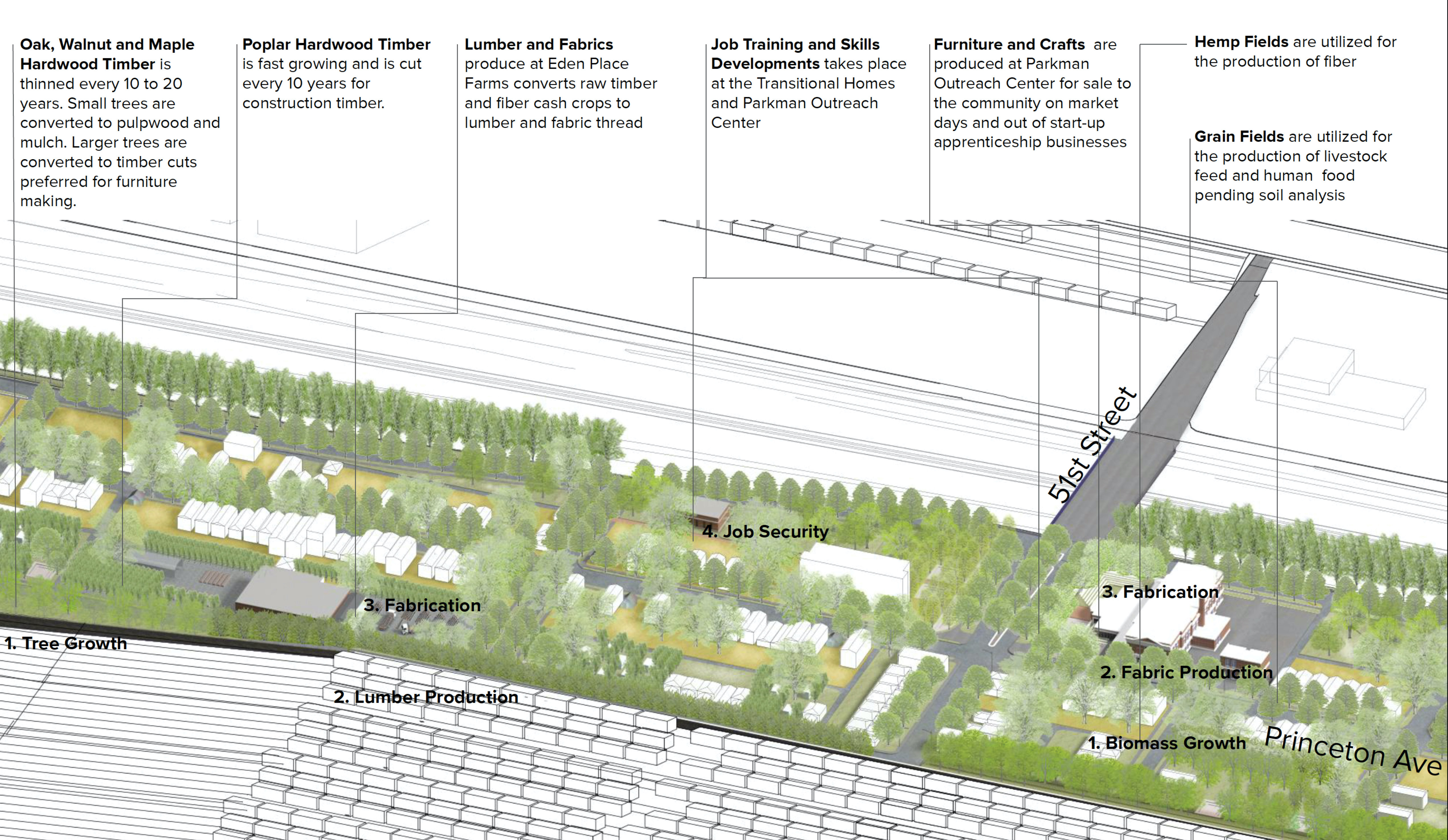

Another group’s proposal for the area around the schools, called Grow Back, uses a phytoremediation strategy to fight soil and air pollution while providing employment and housing opportunities through the creation of a timber forest in Bronzeville. In that proposal, Parkman would serve as an incubator, workshops, and live/work spaces for residents.

“Before we started figuring out our main strategy, we went to the site a few times. When we noticed a large homeless population, we asked for their thoughts about a possible development in the area, and did a donation drive,” says Riya Desai (B.ARCH. 5th Year). “Obviously, they wanted homes, but more than that, they were ready to have any kind of job development. We already planned on planting timber trees as a phytoremediation strategy, but we realized we could look at this as a source of revenue and create these layers of jobs that pan out over 40 years.”

Similarly, two other groups imagined the various vacant lots in the neighborhood as edible gardens, with Overton and Parkman serving as support: the former becoming a seed bank and horticulture museum and the latter a campus for urban farming with commercial space.

To help students form their proposals, Cox and his team from the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, along with developer Ghian Foreman, provided guidance. Cox was instrumental in grounding the studio in the realities of what was happening in regards to city government. Foreman, meanwhile, is president and chief executive officer of the Emerald South Economic Development Collaborative, and provided meaningful insight into ongoing community efforts in the area.

Likewise, students worked with community groups such as Eden Place Farms and Lodebar Church and Ministries to get a better understanding of the community’s needs and how they were affected by the closing of both schools.

“To be on the ground with some of the people we talked to this past semester, it’s eye-opening. We had to listen to the people there in the community,” says Samuel Bautista (B.ARCH. 5th Year). “It stressed to me that our proposal cannot impose something that limits people to do one thing, a way for people to get the basic infrastructure for what they need and a way for things to blossom from there.”

Together, professors, students, city officials, developers, and community members participated in a process where ideas nursed in academia can contribute to the conversation about how to revitalize the former Overton and Parkman schools and their outlying areas.“As part of this academic exercise, one of the most moving intellectual propositions was to understand that to overcome school closures was not going to be the result of independent reopening actions of specific buildings, but rather a systemic rethinking on how to grow back the community landscape. Therefore, we could start tapping into the roots of those social injustices that caused the closures in the first place,” says Villalobos. “Together, abandoned schools, vacant lots, and streetscapes in need of retrofitting could begin to seed long-lasting, collective, and resilient processes toward a more balanced and vibrant urban life.”